Brendan Cogavin C.S.Sp., February 2021

My story

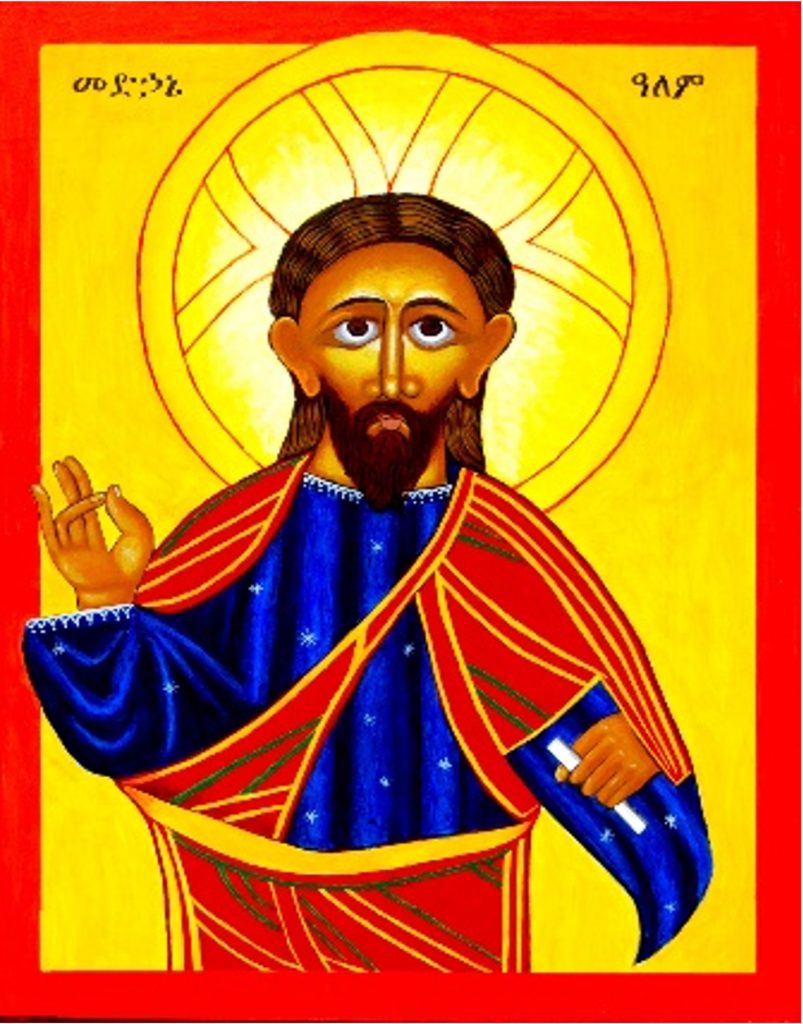

Arriving in 1995, after a year’s language study, I was in a country with – excitingly – different cultures, languages and Christian traditions. I spent the next year in full-time learning of culture, language and religious tradition, regularly attending Ethiopian Orthodox Church (EOC) services and daily catechetical programmes to improve my linguistic skills and to get to know the spirituality and the mechanics of EOC liturgies. This was supplemented through preparatory studies and debriefing with experienced confrères.My regular appearance at church at weekends and my efforts to follow the liturgy in the traditional Ge’ez language culminated, one memorable Ascension Thursday, in an invite by the parish priest to join him and the other clergy in the choir area. I was handed the traditional prayer stick and sistrum and was shown how to use them. A defining moment in my ecumenical journey, this experience encouraged me to participate more fully in the life of local Orthodox Christians, to make a deeper study of their traditions and to continue building up mutual understanding between our two ancient apostolic churches. Any reconciliation and return to communion between our two sister churches involves personal contact at a grass-roots level and a commitment to study and appreciate the spiritual riches of the Ethiopian Church. I decided to concentrate on studying and practicing Ethiopian iconography – both as an academic pursuit and as a practical activity (e.g. producing Ethiopian illustrations for Ethiopian Catholic liturgical books).

Calendar 2021 Images

Click to enlarge

Calendar 2021 Images* for May (Holy Saviour), August (Assumption) and December (Our Lady and Beloved Son).

Ethiopian Church History – in a nutshell!

The evangelisation of Ethiopia pre-dates that of Ireland by over 100 years. In the era of St. Athanasius of Alexandria (of Council of Nicea fame), the first bishop was appointed to the kingdom of Axum; hence, the large Egyptian influence on Ethiopian Christianity. (Many foreigners still wrongly see the church here as Coptic!!). This continued until 1959, when – under Emperor Haile Selassie’s leadership – the first Ethiopian-born Patriarch was elected and the EOC became self-governing (auto-cephalus). A second wave of evangelisation took place in the late 5th century. The Nine Saints, a group of missionaries from the Syrian heartland who introduced monasticism, were important in the initial growth of Christianity in what is now Ethiopia. Both missionary movements left their mark in terms of liturgy, art and architecture. Just as Irish Christianity evolved over centuries, so too did Ethiopian Christianity but it retains its own distinctive character to this day as there were no major attempts to force it to confirm to an outside model.

In the 16th and 17th centuries there were sporadic outside contacts, notably with Portugal and through the Jesuits (this did not end well). The legends of Prester John (Priest King) of the Indies pushed the King of Portugal to try to form an anti-Islamic alliance with the Kingdom of Ethiopia. Francisco Alvares, a missionary who accompanied Portugal’s Ambassador, left an account of his Ethiopian travels, including the first detailed description of Axum and Lalibela. Some of the European religious art of that ambassadorial party influenced Ethiopian religious painters, contributing to Ethiopian art’s melting pot.

Principal Ethiopian Art periods

In general, until the contemporary era, most religious art was developed in monasteries. Art took many forms including architecture heavily influenced by Syrian basilica-style models and the classical, round churches typical of the highlands. Churches were decorated from top to bottom in painted murals depicting biblical narratives and saints’ lives plus decorative painting of the roofs and other architectural features. Manuscript calligraphy and illuminations are highly developed. The patrons for such work were the local nobility or imperial court. In addition to murals, small individual icons were also commissioned.

1. Axumite Period (4th to 8th centuries)

Scholars remain interested in tracing the development, techniques and sources of the EOC, using the extensive literature that documents its iconography. Archaeologists and art historians continue to scour the remote northern mountains to document the rich patrimony before it is lost forever. Latest carbon dating evidence has indicated that, in a remote monastery dedicated to Abba Garima, two gospel books, estimated to date from 390 – 660 AD, could be the world’s oldest illustrated Christian manuscripts!

2. The Early Solomonic period (1270-1527)

This features Lalibela’s internationally famous twelve rock-hewn churches, numerous murals and illuminated manuscripts as well as rock-hewn churches outside the main complex and scattered nearby. The artwork, possibly by Coptic artists resident in the royal court, is still mainly Coptic in style.

3. The 2-style Gondarine period (1632-1769) – a period of relative political stability

The royal court moved regularly around the kingdom to ensure the loyalty of all the aristocracy. With increased political stability, in large part arising from the establishment of Gonder as a permanent royal settlement, art flourished. The first Gondarine style saw the use of bright colours, the absence of shading, clothing (accentuated with complex decoration) painted in red, blue or yellow with the folds shown using simple parallel lines. Contours are well-defined and faces are painted using red. The principal art works during the whole period are murals and portable icons – including many diptychs and triptychs. Works painted in the second Gondarine style (c1730-1755), have darker shades of color; contours become lighter, and more delicate shading gives volume to the bodies and faces of the figures. Various new themes, many inspired by books printed in Europe, appear during the eighteenth century.

4. Late Solomonic (mid-19th to mid-20th century)

This period sees some forays into a more realistic and less idealized style. Perhaps ‘the golden age’, When people think of Ethiopian Church art, this period immediately comes to mind, especially because artists who cater for the tourist trade have embraced this style and made it popular.

5. Contemporary Period (post-Imperial)

Despite the fact that many modern Orthodox have adopted a more Western-influenced style, the themes represented are still Ethiopian and the overall schema is traditional. Many modern churches are being painted by painters trained in Addis Ababa University’s School of Fine Arts. Technique is properly executed unlike in some Catholic churches, where very large amateur paintings prominently displayed, copied from photographs, do not contribute to the liturgical space and, in fact, distract from the liturgy.

Conclusion

I hope that Ethiopian-rite Catholic churches will follow the lead of Abba Musie (Moses) Bishop of Emdiber, who decorated his cathedral from top to bottom in Ethiopian iconography. Collaborating with him for over 20 years, I wrote at his behest a chapter of his book (presenting the church decoration’s various parts), arguing that Ethiopian sacred imagery is a treasury of riches to be re-opened for Catholics.

* Each month of the Irish Province’s 2021 Calendar is illustrated by an icon.